Difference between revisions of "Reorte (Rough Guide)"

Disembodied (talk | contribs) m |

Disembodied (talk | contribs) m |

||

| Line 24: | Line 24: | ||

As old gods are consumed in this constant warfare, new ones arise to take their place. The ziggurats are not viewed as representations of the conflict; rather, they are real-time indicators of the supernatural power-struggles taking place below. The ziggurats are stable enough to withstand all but the most shattering of seismological events: the clay statues, however, are not, and there’s a regular attrition as gods are shaken off their steps, smashed by falling debris from a higher deity, or just shuddered to pieces where they sit. No statue, no god, no cult; the Theocracy opens to new members, and the surviving gods move up to fill the empty places above them. There’s always a steady stream of new divinities waiting in the wings: at least, until that happy day arrives – may it come soon! – when only one god sits atop one ziggurat, and no new sculptures can be found anywhere to challenge its supremacy. |

As old gods are consumed in this constant warfare, new ones arise to take their place. The ziggurats are not viewed as representations of the conflict; rather, they are real-time indicators of the supernatural power-struggles taking place below. The ziggurats are stable enough to withstand all but the most shattering of seismological events: the clay statues, however, are not, and there’s a regular attrition as gods are shaken off their steps, smashed by falling debris from a higher deity, or just shuddered to pieces where they sit. No statue, no god, no cult; the Theocracy opens to new members, and the surviving gods move up to fill the empty places above them. There’s always a steady stream of new divinities waiting in the wings: at least, until that happy day arrives – may it come soon! – when only one god sits atop one ziggurat, and no new sculptures can be found anywhere to challenge its supremacy. |

||

| − | Theogony is a fine art on Reorte. The inhabitants are prone to fits of eche, dreamlike states where they glimpse the sacred outlines of a new god, and grasp the essentials of its cult. From this vision they produce a clay sculpture, and set it off on its progress up the tiers. Some offworld xenologists have claimed that eche is actually just a neurophysiological event triggered by the electromagnetic fields resulting from the grinding, shifting tectonic plates. The Reortese dismiss this as mere superstition; gods rise and fall again, and the ground continues to shake. There is admittedly a tendency for the more long-lasting and powerful cults to be based around broad, squat gods, with low centres of gravity and few projecting appendages, but to the Reortese these attributes are simply indications of divine strength and potency. Thin and spindly gods do exist, but they do not stand up well to the rigours of subsurface combat; hence their statues seldom climb very far up the ziggurat steps. |

+ | Theogony is a fine art on Reorte. The inhabitants are prone to fits of ''eche'', dreamlike states where they glimpse the sacred outlines of a new god, and grasp the essentials of its cult. From this vision they produce a clay sculpture, and set it off on its progress up the tiers. Some offworld xenologists have claimed that ''eche'' is actually just a neurophysiological event triggered by the electromagnetic fields resulting from the grinding, shifting tectonic plates. The Reortese dismiss this as mere superstition; gods rise and fall again, and the ground continues to shake. There is admittedly a tendency for the more long-lasting and powerful cults to be based around broad, squat gods, with low centres of gravity and few projecting appendages, but to the Reortese these attributes are simply indications of divine strength and potency. Thin and spindly gods do exist, but they do not stand up well to the rigours of subsurface combat; hence their statues seldom climb very far up the ziggurat steps. |

They are a tough and fatalistic people, the Reortese, inured to suffering, content with very little by way of material goods. Their towns and villages are collections of low huts and lean-tos, constructed entirely from the ubiquitous rubbery Fervid Vetch trees which they carefully train and pull together to form springy hammock-dwellings, suspended in pockets of greenery close above the shaking ground. These may bounce and sway, but they easily survive the daily tremors. And if a major shock should come, and tumble the town, the fast-growing trees soon reappear and the survivors resume their lives with no more than a shrug and a shake of the head. |

They are a tough and fatalistic people, the Reortese, inured to suffering, content with very little by way of material goods. Their towns and villages are collections of low huts and lean-tos, constructed entirely from the ubiquitous rubbery Fervid Vetch trees which they carefully train and pull together to form springy hammock-dwellings, suspended in pockets of greenery close above the shaking ground. These may bounce and sway, but they easily survive the daily tremors. And if a major shock should come, and tumble the town, the fast-growing trees soon reappear and the survivors resume their lives with no more than a shrug and a shake of the head. |

||

Revision as of 23:25, 28 August 2008

Reorte

- Economic status: Poor Agricultural

- Technology level: 6

- Population: 3.1 billion Black Fat Felines

- Political status: Dictatorship

- Radius: 6419 km

- G: 1.03 standard

“This planet is mildly fabled for its inhabitants’ eccentric love for tourists but plagued by deadly earthquakes.”

“Reorte”, in the old, high Narrow Speech, means “Lair of Gods”. The planet certainly seems to be infested with them, and hundreds of new ones are discovered every week.

Perhaps it’s not surprising that the inhabitants of one of the most seismically active worlds in the whole eight galaxies should be so fervently religious. They are forever at the mercy of titanic hidden forces, utterly beyond their control, and the tremulous ground is a constant reminder of vast, immanent presences beneath their feet.

For reasons of safety, then, Fennervich, the main shuttleport on Reorte, is situated on the most reliably solid territory available – at the south pole, in the middle of the ice-sheet. Reorte has virtually no axial tilt, and hence no seasons, so although the temperature at Fennervich seldom gets much above 250° absolute it’s climatically very stable. The air is clear and calm, but there’s not a lot to see on the drop down – just endless empty ice.

Fennervich shuttleport is welcoming, though, and friendly, once you’ve scurried across the icy landing pad through the strange perpetual dawnlight to get inside out of the biting cold. Outworlders, “sky-born”, of any sort, are viewed with a deep and reverential respect. One thing you can say about the Reortese, they’re a very hospitable species. Partly it’s cultural: a superabundance of natural disasters has made their society strong on the support of strangers. But mainly it’s down to the one constant in their complex, ever-shifting theology: their strong and abiding dislike of their own gods.

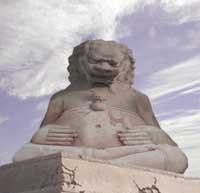

According to the Register, Reorte is a Dictatorship. Technically speaking it’s actually a Theocracy, controlled by a fluctuating priesthood. Entrance to the priesthood is relatively easy: first, you discover a god; then you formulate its cult; finally you erect a statue of your new god on any available space on the bottom step of your local ziggurat, and Hey Priesto, you’re a member of the Theocracy! Every community is centred on a low, broad, three-tiered and six-sided ziggurat, adorned with monumental clay models of the local gods: eighteen on the bottom tier, twelve on the second, and six on the summit. The higher up a statue sits, the more authority its cult possesses.

Reortese gods are dwellers in the underworld, locked in a never-ending, world-shaking battle for dominion – a battle which is, to say the least, inconvenient to the surface inhabitants. Reortese worship is based around the hope that eventually, perhaps, one god might achieve a final victory, to reign alone in the World Beneath and leave them all in peace. Until then, the gods’ chthonic brawling must be endured: the ultimate neighbours from Hell.

As old gods are consumed in this constant warfare, new ones arise to take their place. The ziggurats are not viewed as representations of the conflict; rather, they are real-time indicators of the supernatural power-struggles taking place below. The ziggurats are stable enough to withstand all but the most shattering of seismological events: the clay statues, however, are not, and there’s a regular attrition as gods are shaken off their steps, smashed by falling debris from a higher deity, or just shuddered to pieces where they sit. No statue, no god, no cult; the Theocracy opens to new members, and the surviving gods move up to fill the empty places above them. There’s always a steady stream of new divinities waiting in the wings: at least, until that happy day arrives – may it come soon! – when only one god sits atop one ziggurat, and no new sculptures can be found anywhere to challenge its supremacy.

Theogony is a fine art on Reorte. The inhabitants are prone to fits of eche, dreamlike states where they glimpse the sacred outlines of a new god, and grasp the essentials of its cult. From this vision they produce a clay sculpture, and set it off on its progress up the tiers. Some offworld xenologists have claimed that eche is actually just a neurophysiological event triggered by the electromagnetic fields resulting from the grinding, shifting tectonic plates. The Reortese dismiss this as mere superstition; gods rise and fall again, and the ground continues to shake. There is admittedly a tendency for the more long-lasting and powerful cults to be based around broad, squat gods, with low centres of gravity and few projecting appendages, but to the Reortese these attributes are simply indications of divine strength and potency. Thin and spindly gods do exist, but they do not stand up well to the rigours of subsurface combat; hence their statues seldom climb very far up the ziggurat steps.

They are a tough and fatalistic people, the Reortese, inured to suffering, content with very little by way of material goods. Their towns and villages are collections of low huts and lean-tos, constructed entirely from the ubiquitous rubbery Fervid Vetch trees which they carefully train and pull together to form springy hammock-dwellings, suspended in pockets of greenery close above the shaking ground. These may bounce and sway, but they easily survive the daily tremors. And if a major shock should come, and tumble the town, the fast-growing trees soon reappear and the survivors resume their lives with no more than a shrug and a shake of the head.

Outworlders are always welcome, although Reorte’s tourist industry could not be called well-developed. The frequent Changing of the Gods ceremonies are colourful and picturesque, but apart from the ziggurats there are few places on the planet permanent enough to be called “attractions”. The real chance of getting caught in a major earthquake can also be offputting to the casual visitor.

Surprisingly, very few Reortese seem to want to emigrate from their unstable homeland. They might admire visitors from other worlds with quiescent deities, and envy those who have renounced planetary life altogether to dwell in artificial structures suspended in the pure and empty vacuum of space; but in general they are unwilling to abandon their fellows to suffer their gods’ disturbances unaided. Reorte, it is true, produces many volunteers for the Galactic Navy, and the Space Marines’ famous G Division contains a high proportion of Reortese recruits. Even here, though, most veteran survivors choose to return at last to the planet of their birth, to pick up again the burden of their people and wait for the day when their world will be free of the tumult from beneath.

Are they noble? Are they foolish? During my stay, the fat and conical god Heserach, whose stamina and endurance had kept him atop the Kittering ziggurat for more than three generations, tumbled and fell. Many Reortese had hoped that here, at last, might be a god who could triumph over all the rest: now he lay in pieces on the broken earth. A silence filled the dusty air; no-one moved. Then Heserach’s High Priest coughed, and grunted, and spat upon the ground, and with a well-worn broom began to sweep the rubble of his god away. The other townspeople sighed, brushing dust from their fur, and made a quick headcount of their friends and kinfolk before turning to rebuild their homes anew. Are they noble? Are they foolish? Are they both? Or something else entirely?